In recent years we’ve seen an increase in focus in mainstream media towards mental health issues. I’ve used the outdoors as a way of managing my stress levels and look after my mental health for years so I’ve harbored latent thoughts that they are linked. In October 2018, the Guardian ran an article about a Doctor in the Shetland islands writing “nature prescriptions” for chronic and debilitating illnesses and I was convinced I might not be the only one to notice the connection.

My over caffeinated leg bounced up and down as I scribbled onto a pad some ideas for blog posts at the end of last season. The ideas flowed so easily from my mind to the paper and in my optimism, I thought I could pump out a post a week. More maybe if I got into good flow and found some free time to hot desk free from distractions. As you can probably guess, my optimism proved to be unwarranted.

Part of my issue has been my determination not to write a wishy washy preachy opinion piece with no imperial evidence. I’m not a huge fan of pseudoscience at the best of times, but especially around health issues. I wanted to be sure that what I’ve experienced over the last 15-20 years isn’t just unique to me and that it has been repeatably found and studied and peer reviewed. Whilst my experience, I feel, is extremely valid, it isn’t reliable. I wanted to follow the data and the research… but that’s a long thread to start pulling on!

My conclusion has been that this clearly isn’t a one blog wonder and as such I’ll be writing a bit of a series looking at and trying to make sense of the role of outdoors, adventures and specifically packrafting can play in tackling the rising issue of mental health in modern western culture.

So where to start! Maybe the best place to start is my experience as a way of framing my mind set going into my research. I’ve been working as a guide and instructor in the outdoors since 2005. This is a bit of a rarity in that most of my peers who started at the same time as me moved on to get proper jobs and contribute in a more meaningful way to society. I of course thought for a long time that I would eventually do the same, but I realized I was a lifer after about 4 or 5 years. My career has seen me work on every continent and work in some beautiful and challenging environments from working in extreme altitudes on various mountains to remote and unsupported expeditions. I’ve been a canyoning guide, a climbing instructor and generally taken people hiking, biking and paddling all over the world. A younger, fitter, more ambitious version of me was a sponsored expedition river runner, putting a series of first descents in around the world for a few years. In short, I’ve been obsessed with the outdoors, particularly rivers, for a long time. They’ve been my place of work, where I train, where I go for fun and critically where I go when I’m facing issues or trying to figure out problems.

I think the reason the outdoors has become such a defining feature of who I am is because I’ve had some truly profound experiences. Not all of them epiphanies or flashes of brilliance that have made indelible impressions on me. Many of these profound moments weren’t really moments but might have been entire seasons or expeditions where, upon reflection I’ve noticed changes within myself, my outlook, my quality of character and sense of self. The recognition of this, although subconscious at first, has lead me to lean on adventure at times of hardship or grief, or desperation as my crutch. Getting out into wild places has a palpable restorative value for me.

As an outdoor educator, this self development was part of the experience we strived to impart on our students and whilst their exposure to these benefits were obviously shorter, the effects would be tangibly seen regularly.

I’ve ruminated on this profoundness and have it as one of the leading principles of the experiences we seek to create with packrafting Queenstown.

In the interest of full disclosure, as I’ve suggested, there have been times in my life where I’ve need this crutch to lean on. I’ve experienced depression of varying levels for periods of my life the way I’ve dealt with this most successfully has been through adventure. So I guess this frames the way that I have come to write these blogs. Much of the research I’ve been looking at has been focused on anxiety, the most commonly reported mental health issues. Whilst I can’t claim to have an intimate relationship with anxiety or ever really suffered from problematic anxiety or panic attacks, there is a close relationship between depression and anxiety, so the research rang true to me as I ran it through my “Bullshit Register”.

As I mentioned from the beginning, I’ve tried to look at mental health in the outdoors in a few different ways. So for this particular blog I wanted to look at one aspect of modern life that has been sited as a contributing factor to the growing mental health issues we are collectively facing; our relationship with technology, specifically our phones. Escaping into the wild seems like an obvious way we can have healthier relationships with our laptops, phones and tablets. Unplug and have digital detoxes periodically.

Social media in particular has a mechanism for creating damaging cycles, especially to those more naturally pre-disposed to heightened anxiety or depression. We can find ourselves feeling anxious whilst on social media, comparing our lives to perfect images of other peoples lives projected online, or arguing with trolls over trival matters. To make us feel better, our brains crave a release of neurotransmitters like serotonin or dopamine.

“Dopamine is a chemical produced by our brains that plays a starring role in motivating behavior. It gets released when we take a bite of delicious food, when we have sex, after we exercise, and, importantly, when we have successful social interactions. In an evolutionary context, it rewards us for beneficial behaviors and motivates us to repeat them.” (Trevor Haynes, 2018)

How do we seek dopamine? Through checking our phones or scrolling through social media. These dopamine hits can end up taking the place for the dopamine hits we get when we spend time in the real world with friends and as such can lead to a drop in motivation to spend time with people in the real world. Over time this can lead to isolation and loneliness. The depression caused by this loneliness drives us to seek dopamine… and the whole cycle starts again, spiralling into a worsening state of mental health. This dopamine loop is similar to what gambling addicts will experience, known as Behavioral Addiction. It is of little surprise that it can be destructive.

The issue is wider than just social media though. Phones tempt us into multi tasking. We never leave the office and have the world at our finger tips. This obviously has huge benefits and can be a really useful tool for us all. However, the ease with which we can be contacted or the variety of tasks that we can now accomplish simply by pulling our phones out and tapping away, means that it’s extremely easy to simply never swtich off.

This multitasking puts huge amounts of stress on our brains. Around 2% of us are wired to be effective multi taskers (Strayer, 2017) the rest of us are now taking on a multitude of different tasks, worrying about all of them, and more than likely spending less attention on any single task than it deserves. There are a wide number of negative effects from multitasking such as increased cortisol (our stress hormone), increases in human error, higher chances of being involved in an accident, becoming more distracted but perhaps the most significant is the stress it puts our Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) in our brain.

The excessive demands we are putting on our PFC can lead to fatigue, like with a muscle that is being over used. It ceases to function as well as it should. The PFC is also responsible for a number of vital task such as, critical thinking, problem solving, decision making, strategic planning and impulse control (Strayer, 2017). So it’s a vital part of our brain to be working at less than optimal levels.

None of this makes for very encouraging reading. We are trapped in addictive and isolating cycles of social media and are reducing our ability to undertake cerebral and logic based tasks such as critical thinking. Yay!

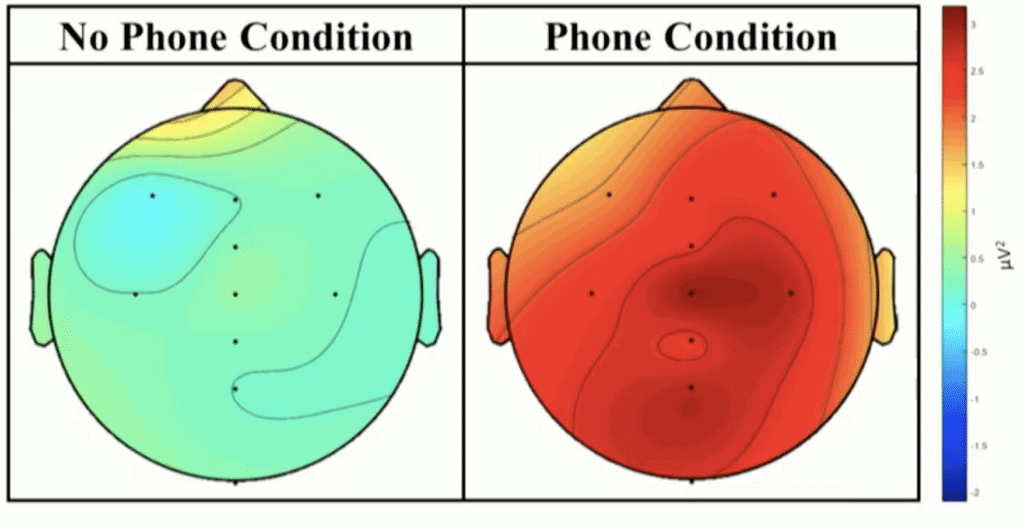

The good news is there are a number of ways we can find solutions to these problems. Here comes the science bit, concentrate. Dr Strayer, a professor of Cognitive Neuroscience spent over 10 years studying brain-based measures of cognitive restoration. In his study he looked at the impacts of both short term and long term exposure to the natural world. The short term study involved having two groups of participants take a walk through a park. One group were asked to use their phone as they walked, the other group handed in their phones prior to the experiment. By using a electroencephalogram (EEG), they were able to measure the level of electrical activity in the brain, paying particular attention to the anterior cingular cortex. Twenty minutes after the experiment ended, the result showed startling differences suggesting there is a kind of technology hangover as a result of our multitasking on our phones.

The green areas on the images below indicates the brain is rested, the red areas show areas of intense electrical activity. Additionally, participants who were on their phones were only able to recall about 50% of what they’d seen on their walk. As you might expect, the longer term study showed the same trends but with increased benefits of demonstrably increasing short term memory, working memory, better problem solving, greater creativity, lower levels of stress, and higher feelings of positive self esteem. Because science.

Stepping away from the research for a second to bring it back to my own personal experience, I’ve found that not only spending time in these special wild places, but also taking on a challenge or something new exponentially increases the restorative effect of adventure. When I notice unwanted behaviours or thoughts starting to form habits, or I’m working through some problems I have always taken it to the river.

Anxiety or, in my case, depression often arise from either fixating on the past or worrying about the future. Perhaps both. Thoughts can form patterns in your brain. Much like water flowing over sand, over time, an established path is formed. The path for someone suffering from depression often leads to two parts of the brain known as the default mode network or DMN. The DMN helps create a sense of who we are by looking at the past and projecting our experiences to the future. The more time we spend in the DMN, the more established that pattern becomes and it can be a difficult loop to break. For me getting on the river, especially if I’m paddling something challenging forces me to break the cycle. My mind is 100% in the present. The past or the future don’t feature in my mind. Nothing else exists but my next few paddle strokes. I’m not worried about my mortgage, getting an average review on trip advisor, the up and coming meeting or that crushing guilt that all fathers will know when they spend time away from their young family. All that exists in those moments is my cross current speed, the angle of my bow, the resistance on an active blade, the power of the current and my brain processing hundreds of points of information to tell my body what to do next. It’s almost meditative. Everything else goes and there’s a singularity of focus.

Not only does this stop the re-enforcement of negative thoughts, it breaks it with something provides me with a sense of pride for overcoming challenges or nailing my line, or achievement after summiting that mountain. There is zero multitasking.

There are other benefits too. Adventures create opportunities to develop extremely close bonds with those with you. There in often lies the profoundness, in the meaningful human interaction or long conversations around the camp fire, the deep trust knowing that you’re watching each others back. The relationships that I have forged in those environments are more often than not the most meaningful and long lasting in my life which long term helps combat isolation and decrease the chance of me seeking dopamine hits online. To frame the importance of those relationships in such clinical language under plays the magnitude of emotional resonance of these relationship. Having and sharing these experiences of freedom, of exploration and overcoming challenges with people, for me, is the source of some of the greatest joys in life. It anchors me, connects me and allows me to see who I really am and reflect on what I’d like to do better.

Adventures can build good habits such as allowing yourself to be (physically or emotionally) vulnerable, accepting the unknown, building resilience and adapting to change. Given the rate of change within our society is accelerating, the ability to adapt well to changes is going to be an important skill for not just us, but the even more so for the next generation to come.

Depression and anxiety are hardwired and cannot be gotten rid of. By creating an experience where we can live with anxiety and battle depression, we can experience it and NOT have it rise to detrimental levels. That’s pretty powerful.

Our overnight trips strive to create these profound digital detoxes. It’s easy to over look the importance of looking after you mental health, but a trip into the wild with your loved ones, your colleagues, your family should be high on your list for ways to look after yourself.

Alternatively, if you’re seeking a way to make your relationship with the outdoors a lasting one, book onto our courses. In addition to spending a couple of nights “unplugged”, you’ll learn skills and knowledge that will set you up for years to come, taking your backcountry adventures to the next level. Discover the meditative quality of navigating rivers.

In our next blog we’ll be looking at adventure and vulnerability and how it can lead us to develop positive characteristics and help is lead happier, more fulfilled lives.

I will also be writing a blog on some on the changing roll of adventure for me as my life has changed by becoming a father.

Hi Huw – nice article – I found inspiration in it. If I’m ever over NZ way I’m in for some packrafting.

All best – Ben M (skyline L2Ps)

Good on ya Ben, we’d love to have you on the river if you ever get out this way

Interesting reading – Thank You Huw (must get off my phone now!!)

Thanks Helen!