As the third and final article in the series as part of the Packrafting Culture of Safety movement, we’re examining hypothermia. If you haven’t read the previous two articles, it might be useful to go back and read them first. We’ve examined how we die in the water in an attempt to build risk literacy and provide a deeper base of knowledge that might inform our decisions and behaviours whilst we’re on the water.

So you’ve survived drowning, you haven’t inhaled water during the cold water shock phase of falling into the water and you haven’t succumbed to autonomic conflict. Great work! Now what’s killing you next? The cold.

So why is hypothermia a big deal for packrafters? Two primary reasons are the nature of the activity and the remote setting it will often take part in. Given the water based elements of packrafting, there is a heightened risk of submersion/immersion in water or simply just getting wet as we’re paddling. If we think back to school physics lessons hopefully you’ll be able to remember the basic ways in which heat loss occurs

Radiation– Heat radiating out from the body when the environment is colder than it is.

Convection– The movement of heat through the air or currents.

Conduction– The movement of heat through direct contact

Evaporation– Heat loss in the form of energy transfer needed to vaporise water. Water does not need to boil to evaporate; evaporation will occur close to 0°C. Energy is needed to break the molecular bonds which come from the heat of the ambient air or the surface the water is in contact with. The greater the difference in temperature between the surface and the air, the greater the heat loss from the surface.

Respiration– There are two heat losses in this process; the introduction of cold air during inhalation cools the core through convection and also as moisture inside the lungs is evaporated and exhaled.

Being on the water our primary mechanism of heat loss that we are worried about is conduction. As you sit and read this, chances are that you are losing body heat through radiation and potentially convection if there’s a bit of a draft. In the water however conduction will strip heat away from our bodies far more efficiently. It’s not twice as effective or even ten times more effective, your body will lose heat twenty five times quicker in the water. That’s ludicrously quick.

The remote nature of some packraft trips can mean that help is not going to be quick in coming (if at all) and any and all issues and incidents will have to be dealt with in the field. This can be tricky and often the conditions that lead to the creation of hypothermia or potential hypothermic state are still present in the field. Time is not on our side and although the initial onset of mild hypothermia can be slow, the acceleration into moderate and severe hypothermia is cause for concern. In an open water setting where it is possible to be exposed to a prolonged immersion, even mild hypothermia can lead to swim failure and the cause of death is drowning…. but the cause of the cause of death may be the cold. Muscles will cease to function properly when they hit a critical temperature of 27 degrees celcius (that’s 80 fahrenheit in old money). In 12c (55f) water muscles can reach this critical threshold in about 20 mins, at which stage only a suitable PFD (personal floatation device) is going to buy you more time in this world. If the muscle tissue in your heart reaches 27 degrees then it’s game over and your end point will likely be myocardial infarctions (heart attack).

So let’s get into it! What is hypothermia?

Hypothermia is pretty tricky to define. In the olden days we might have descirbed hypothermia as a core body temperature below 35c, but there has been a move away from this definition as there is a significant variation between core body temperature of individuals. This definition for us was of limited import as it’s hard to get an accurate core temperature in the field. A glass thermometer is likely to break and is not that accurate aurally. I doubt you’ll be thanked for taking a more accurate rectal reading, especially if the glass is broken. Tympanic thermometers are not great for detecting colder temperatures, especially in wet ears. Your best bet is cheap digital refrigerator thermometer in the armpit of your casualty. It should be noted that even using a non invasive digital thermometer, the actual reading should not be given too much import, the trend over time is more useful as an indicator as to the effectiveness of your treatment. Medical definitions of hypothermia have moved to:

“A medical emergency that occurs when your body loses heat faster than it can produce heat, causing a dangerously low body temperature.”

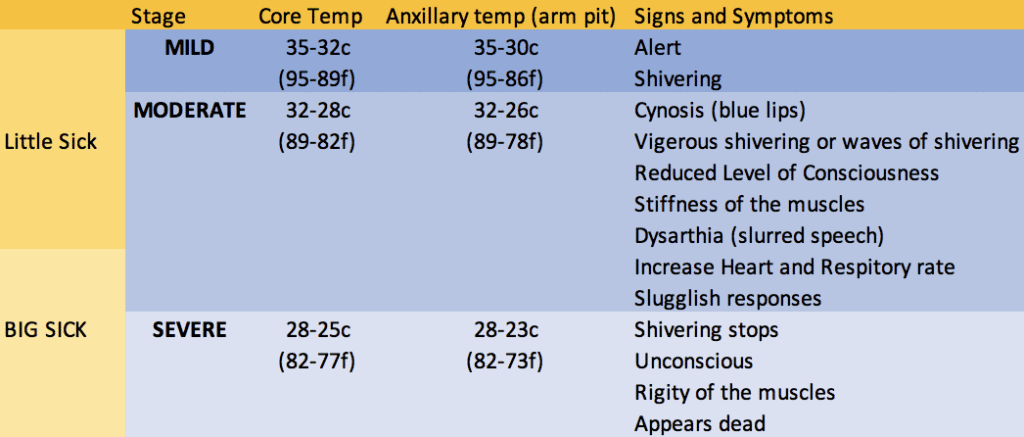

Better than relying on a number to determine your cause of action, treat your casualty as they present to you clinically and do treat it as a medical emergency. Whilst just being a little bit cold is “little sick” (i.e. not too much of a big deal) this can turn into “Big Sick” fast.

Sweet, so we can now look at our paddle partners and judge, based on how they look and appear to us, how hyperthermic they are (because lets face it, if you’re not a professional or part of rescue team, are you really going to carry a thermometer when you’re trying to save weight?!). Now what, how do we treat them?

In terms of treatment, our first priority is to ourselves as a rescuer, the rest of our party, then our casualty. If one member of your group is showing signs of hypothermia, chances are they are not the only one starting to get dangerously cold. So prevention of further escalation is important. Military medics often talk about win the fight first then the medicine and this is a similar approach. The only thing worse than a dead packrafter is a team of dead packrafters. You want to do what you can to remove your team and casualty from the environment that has made them cold. Think about those mechanisms of heat transfer and generate ideas to prevent further heat loss through each mechanism.

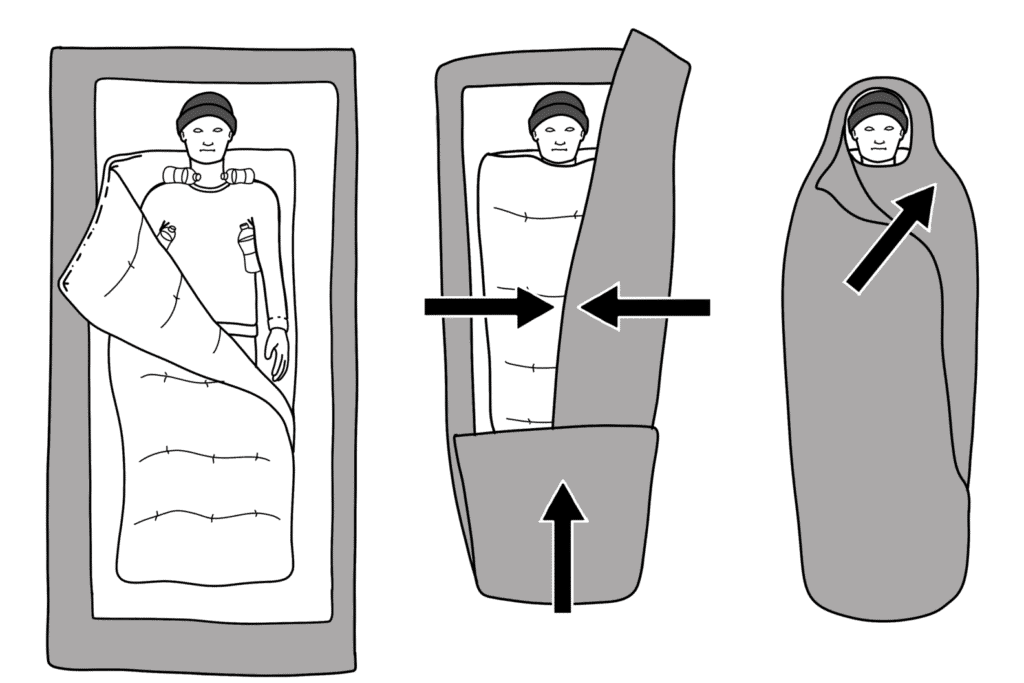

Radiation- Insulation will help trap some of the heat your body is radiating to keep you warmer. For a mild casualty this could mean just putting more clothes on. For a moderate/severe case this could mean a hypothermia wrap a.k.a The Burrito Wrap.

Convection- Can you get out of the wind? Using the packrafts as a wind break has worked for me in the past during a lunch stop. If you’re looking at a “Big Sick” casualty you’ll want something more robust than this. Throwing up a group shelter or tent is a good idea.

Conduction- Are they still in wet clothes? Do you have some dry clothes you can change them into? This is not going to be a good idea for more severe cases where rough handling and agitation can lead to ventricular fibrillation, but more on this later. Insulate your casualty from the ground with a sleeping mat, or whatever you can improvise. Incidentally, conduction is exactly how you’ll lose heat if you follow the now disproven approach of climbing into a sleeping bag with someone. This isn’t all that effective with adults, you’ll just end up with two very cold people.

Evaporation- As above, get them dry if safe to do so don’t vigorously towel dry severe cases.

Respiration- Through rigging up a group shelter or tent and getting as many bodies into the shelter as possible, you will warm the ambient air going into their lungs reducing the effects of respiratory heat loss.

For “little sick” people (mildly hypothermic) one of the most effective heat generating treatments is going to be exercise. Muscles generate heat which is why shivering is an effective natural defense. Due to the number of muscles groups involved in shivering, the effect can be a four or fivefold increase in heat production. Vigorous exercise makes up to 80% of the heat produced in the body, but also competes for the fuel needed to shiver too.

Here’s the conundrum. You can reverse mild hypothermia comparatively quickly through exercise and so this is an obvious and effective early intervention for cold people. However, if you’ve got a moderately hypothermic person their body is displaying a failure in autonomic thermogenesis. They aren’t able to warm themselves and, if they’ve stopped shivering, they’ve run out of fuel. This can go south very fast so forcing them into exercise can be either impossible or it can accelerate their decline. Feed them. Feed them sugars first (if this is appropriate given the presents/absents of other medical conditions such as diabetes) as these are processed quickly, then carbs if you’ve got them for a slower release of energy. Incidentally, some of the same symptoms of hypothermia are also present for low blood sugars (lowered level of consciousness, confusion, slurred speech…) so giving them something to eat will help with this too, just incase you’re unsure of what you’re treating. Given the failure in thermogenesis, you might want to think about introducing a heat source too such as hand warmers in strategic places or a nalgene bottle full of hot water (maybe covered with a sock or something to prevent burns).

If you’re thinking your casualty is starting to get “Big Sick” or you can’t see any improvement in their symptoms or axillary temperature, the best treatment is av gas. Call the heli and get them to definitive care in hostiptal. If your casualty is showing signs of failed thermogenesis (stopping shivering) and a lowering level of consciousness, extraction is important but it is important to do it gently. Set your Personal locator beacon off. Once the level of consciousness is dropping to the point of loss of consciousness, feeding your casualty is no longer safe as the airway can become compromised so food works as an early intervention (or better yet, prevention).

One of your biggest concerns with severe hypothermia is after-drop. What can happen is that the heart will move into a bardycardic rhythm where it slows down to below 60 beats per minute. Significant vasoconstriction occurs too which shuts off blood flow to the extremities or parts of the body that are not vital. This combination of blood shunting and low volume of blood movement can create pools of colder and warmer blood. These pools of cold blood will also be stripped of all oxygen by the cells around it and will take on waste products such as lactic acid. Vigorous exercise, CPR or even sitting casualties up, can lead to this cold blood moving into potentially dangerous parts of the body or even dropping core temperature further. There are two way arrhythmia such as ventricular fibrillation might be triggered, by the cardiac tissue reaching that 27c threshold, or bathing the heart in lactic acid and other waste products in the blood. This is why we treat really cold casualties carefully. Treat them like a spinal patient. Think fast and act slow. Plan every stage of your treatment. Maybe you first want to get the group shelter up and warm the ambient temperature before carefully and methodically getting your casualty into a sleeping bag, insulating them from the ground or getting them into a burrito wrap. Think about ways of achieving the best outcomes and treatments with the fewest movements possible. Scissors or sheers are going to be best for removing wet clothing at this stage. For extraction you might decide not to remove them from the group shelter for example, preferring instead to simple take the poles out and use the shelter/tent as extra layers.

Lastly it’s worth pointing out that if you come across a victim and you have no knowledge of events prior to you finding them, they may present to you as dead. Vital signs might be undetectable. However, it has been known for profoundly hypothermic casualties to seemingly “come back from the dead”. Some victims have been strapped to the outside of helicopters and treated as cadavers only to make miraculous full recoveries upon arriving at hospital. The famous example often spoken about in mountaineering circles is Beck Wethers from the ’96 Everest disaster who walked into camp after being left for dead on the side of the mountain. So the old adage goes, you’re not dead until you’re warm and dead. If they still present as dead when you get them to warmer environments, then a doctor will pronounce them dead, until then act on the assumption that you are on a rescue not a recovery.

One thing that hopefully should be becoming apparent whilst reading this is that moderate and severe hypothermia are extremely difficult to treat and that to achieve a good outcome you’ll need things to go your way at every turn. So for me one of the biggest take aways from all of this is that hypothermia should be prevented not treated. This prevention happens in planning, it happens in training and it happens in your informed gear selection. It’s very rare when things go wrong for there to be a singular cause, it is often a series of small oversights, mistakes, errors in judgement or environmental/conditional factors aligning. Rescue 3’s training philosophy is based around gaining knowledge through training, deliberate practice that leads to a bank of experience and then this experience acting as a basis for your solid judgement. It is through pursuing this experience and solid judgement that you’ll be able to notice these factors aligning.

Huw this is a really useful article well done. I’ve learned a lot. Carol

Thanks!

Huw, thanks for another awesome informative article.